Taming the Interface: A Practical Guide to Solving QM/MM Optimization Convergence for Drug Discovery

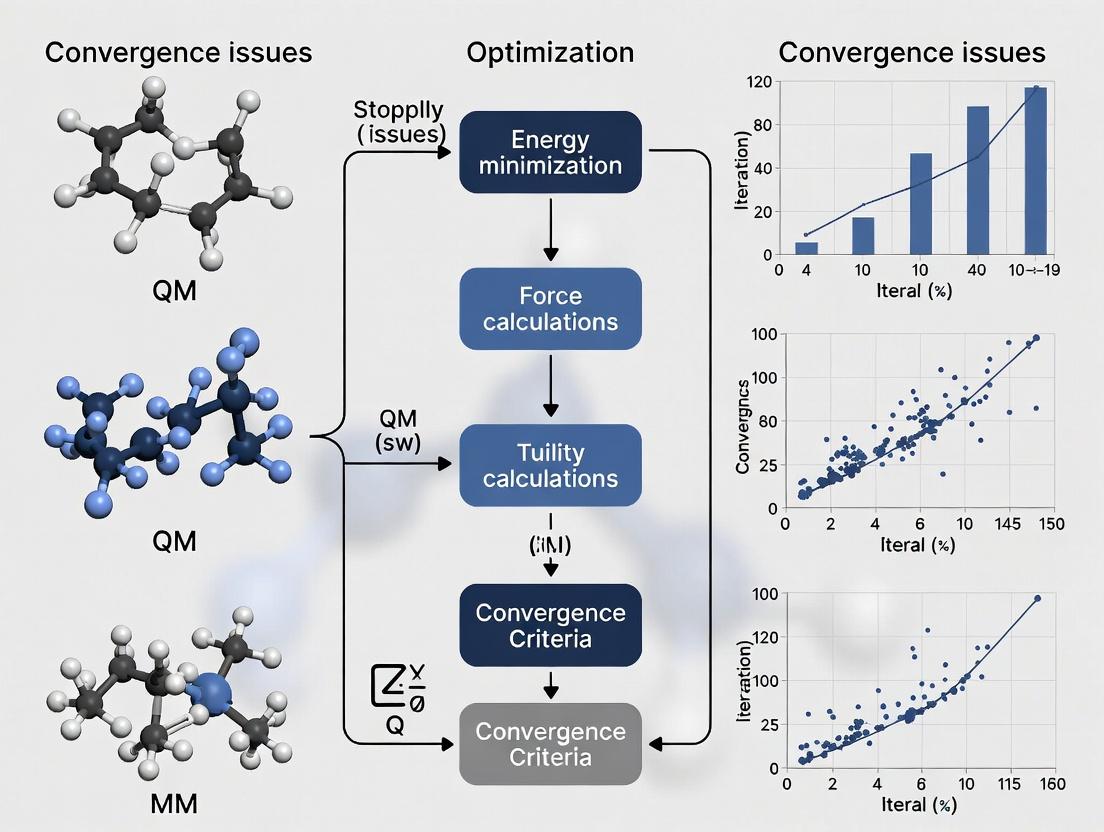

Hybrid Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) simulations are indispensable for studying enzymatic reactions and drug-target interactions, yet convergence failures during geometry optimization remain a major roadblock.

Taming the Interface: A Practical Guide to Solving QM/MM Optimization Convergence for Drug Discovery

Abstract

Hybrid Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) simulations are indispensable for studying enzymatic reactions and drug-target interactions, yet convergence failures during geometry optimization remain a major roadblock. This comprehensive guide addresses researchers and drug development professionals grappling with these issues. We first explore the foundational causes of divergence at the QM/MM boundary. We then detail robust methodological setups and software-specific protocols. A core troubleshooting section provides a step-by-step diagnostic and repair workflow for common failures. Finally, we cover validation strategies and comparative insights on how different QM/MM implementations handle convergence. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to achieve stable, reliable optimizations, accelerating computational biochemistry and structure-based drug design.

Why QM/MM Optimizations Fail: Understanding the Core Challenges at the Quantum-Classical Interface

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue: Oscillating Energies During QM/MM Geometry Optimization

- Symptoms: Total energy or forces fail to converge, showing large fluctuations between optimization steps.

- Likely Cause: Instability at the QM/MM boundary due to (a) link atoms (LAs) passing too close to MM atoms, or (b) erratic shifts in the electrostatic embedding potential as electron density redistributes.

- Resolution Protocol:

- Monitor Boundary Distances: Implement a real-time check for distances between link atoms and nearby MM atoms. Flag steps where any distance falls below 2.0 Å.

- Switch to Smoothed Embedding: Temporarily switch from standard electrostatic embedding to a mechanical or polarized mechanical embedding scheme for 5-10 optimization steps to overcome the barrier.

- Reintroduce Electrostatics: Gradually reintroduce the full electrostatic embedding potential using a smoothing function (e.g., a linear ramp over 5 steps).

- If Persists: Consider redefining the QM region to move the covalent cut farther from the reaction center.

Issue: Excessive Forces on MM Atoms Near the Boundary

- Symptoms: Unphysically large forces on MM atoms within 5 Å of the QM/MM boundary, leading to atomic "jumps".

- Likely Cause: The QM region's partial charges (e.g., from the link atom) creating a strong, localized electric field on nearby MM point charges.

- Resolution Protocol:

- Apply Charge Shifting: Use a charge-shifting algorithm (e.g, charge redistribution) to delocalize the charge on the QM frontier atom over 2-3 adjacent MM atoms.

- Implement a Force Cap: Introduce a temporary, maximum allowable force (cap) on MM atoms in the first solvation shell of the boundary. Remove the cap after the initial convergence stage.

- Validate MM Force Field: Ensure the MM partial charges and van der Waals parameters for atoms near the boundary are compatible with the QM method's electron density.

Issue: Link Atom Induced Strain Artifacts

- Symptoms: Distortion of the QM region's geometry, particularly around the frontier bond, not observed in full QM calculations.

- Likely Cause: The constraining potential (e.g., harmonic bond) between the link atom and the MM frontier atom is too rigid or mis-parameterized.

- Resolution Protocol:

- Optimize Constraint Parameters: Systematically vary the force constant (k) for the LA-MM constraint. Start with a weak constraint (k=50-100 kcal/mol/Ų) and increase only if necessary.

- Adopt a Capping Potential: Replace the simple harmonic bond with a more sophisticated capping potential (e.g., the generalized hybrid orbital (GHO) method) that better mimics the omitted MM atom's hybridization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary source of instability when using link atoms with electrostatic embedding? A: The core instability arises from a feedback loop. The link atom's position and charge are coupled to the QM electron density. As the QM density relaxes, it alters the electrostatic field felt by the MM atoms. Those MM atoms then move, shifting the position of the anchored link atom, which in turn perturbs the QM calculation again. This cyclic coupling can prevent self-consistency.

Q2: When should I use electrostatic embedding versus mechanical embedding to avoid convergence problems? A: Use mechanical embedding (no MM charges in the QM Hamiltonian) for initial, rough geometry optimizations or when scanning very distorted structures. It is more stable but less accurate. Switch to electrostatic embedding for final optimizations and single-point energy calculations on pre-converged structures to obtain chemically meaningful energies and properties.

Q3: How do I choose where to place the QM/MM covalent cut to minimize boundary issues? A: Always cut a single C-C bond. Preferentially cut a bond where both atoms are in the same hybridization state (e.g., sp³-sp³) and in a chemically inert region (e.g., a methylene group in a alkyl chain). Never cut a bond directly involved in the chemical reaction or conjugated network. See the table below for quantitative guidance.

Q4: Are there alternatives to link atoms that are more stable? A: Yes, boundary treatment methods like the Generalized Hybrid Orbital (GHO) or the Local Self-Consistent Field (LSCF) method provide a more theoretically sound and often more stable boundary by using hybrid orbitals to saturate the QM region. However, they are more complex to implement and are not yet universally available in all software packages.

Table 1: Impact of Boundary Distance on Optimization Stability

| Boundary Treatment Method | Avg. Optimization Steps to Converge | % of Simulations Showing Energy Oscillations > 5 kcal/mol | Recommended Min. Distance from Active Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Link Atom (LA) + Full EE | 45 ± 12 | 35% | 4.5 Å |

| LA + Smoothed EE | 38 ± 10 | 15% | 4.0 Å |

| GHO + Full EE | 32 ± 8 | 5% | 3.5 Å |

| Mechanical Embedding Only | 25 ± 6 | 2%* | Not Applicable |

Note: Low oscillation rate with mechanical embedding is due to lack of electronic polarization feedback, not superior stability.

Table 2: Effect of Constraint Force Constant (k) on Frontier Bond Length Error

| Constraint Type (on LA-MM bond) | Force Constant (kcal/mol/Ų) | Avg. Deviation from Full QM Bond Length (Å) | Observed Strain Energy Artifact (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic Bond | 500 | 0.021 | 1.8 |

| Harmonic Bond | 250 | 0.015 | 1.1 |

| Harmonic Bond | 100 | 0.008 | 0.6 |

| Capping Potential (GHO) | N/A | 0.003 | 0.1 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Test for QM/MM Boundary-Induced Instability

- System Preparation: Construct your hybrid QM/MM model, defining the QM region.

- Baseline Calculation: Perform a geometry optimization using mechanical embedding only. Record the final energy and coordinates.

- Electrostatic Embedding Test: Using the optimized coordinates from step 2 as a starting point, begin a new optimization with full electrostatic embedding.

- Monitoring: For every optimization step, log: a) Total system energy, b) RMS force, c) Distance between the link atom and the three closest MM atoms.

- Diagnosis: Plot energy vs. step and distance vs. step. Correlate energy spikes with drops in any monitored distance below 2.2 Å. An unstable run will show clear anti-correlation.

- Iteration: If instability is detected, modify the boundary treatment (e.g., enable charge smoothing) and repeat from step 3.

Protocol 2: Calibrating Constraint Parameters for Link Atoms

- Reference Data: Optimize a small molecule analog containing the frontier bond using a high-level, full QM method. Record the precise equilibrium bond length (R_qm).

- Model Construction: Create a QM/MM model where the small molecule is cut at the identical bond, replaced with a link atom (typically hydrogen).

- Parameter Scan: Conduct a series of constrained QM/MM single-point energy calculations, varying the frontier bond length (R) in 0.01 Å increments around R_qm.

- Energy Fitting: For each chosen harmonic force constant (k), fit the calculated energy points to the function E = 0.5 * k * (R - Req)^2 to find the resulting equilibrium length Req for that k.

- Selection: Choose the value of k that produces an Req closest to the target Rqm from step 1, while maintaining a stable optimization in preliminary tests (see Protocol 1).

Visualizations

Diagram Title: QM/MM Electrostatic Embedding Instability Feedback Loop

Diagram Title: QM/MM Boundary Problem Troubleshooting Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in QM/MM Boundary Studies |

|---|---|

| Hybrid Orbital Capping Kits (e.g., GHO) | Replaces link atoms with hybrid orbitals for a more quantum-mechanically rigorous and stable boundary saturation. |

| Charge Redistribution Scripts/Tools | Automatically delocalizes point charges near the boundary to mitigate strong, artificial electric fields. |

| Distance Monitoring Plugins | Real-time monitoring tools integrated into optimization cycles to flag problematic boundary atom approaches. |

| Tunable Smoothing Functions | Software modules that allow the electrostatic embedding potential to be gradually turned on/off or smoothed near the boundary. |

| Parameterized Capping Potentials | Pre-optimized sets of harmonic or anharmonic force constants for constraining common frontier bonds (C-C, C-N, C-O). |

| Benchmark Suite of Cut Molecules | A curated set of small molecules with pre-computed full QM geometries, used to calibrate boundary method parameters. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Sudden Energy Spikes and Oscillation During QM/MM Geometry Optimization

- Symptoms: Total energy oscillates between high and low values with each optimization step. Atomic forces show large, alternating changes in direction.

- Root Cause: This is often caused by a mismatch between the QM and MM regions at the boundary, leading to discontinuous forces when atoms cross the boundary definition. Another common cause is an insufficiently large QM region, where significant electronic redistribution from the reaction is felt by the boundary atoms.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Plot the total energy and maximum force vs. optimization step. Look for a sawtooth or alternating pattern.

- Monitor the coordinates of key atoms near the QM/MM boundary to see if they fluctuate across the defined cutoff.

- Run a single-point calculation two steps in a row (without moving atoms) to check for inherent energy/force inconsistencies.

- Solution: Widen the QM region to include a complete shell of buffer atoms. Switch from a mechanical to an electrostatic embedding scheme if not already used. Consider using a smoothed (or "link") atom boundary scheme instead of a sharp cutoff. Ensure charge capping schemes are correctly implemented.

Issue 2: Complete Divergence of Optimization

- Symptoms: Energy increases dramatically over several steps, atomic forces become extremely large, and atoms may be displaced to unrealistic positions, causing the simulation to crash.

- Root Cause: This can be due to a large energy gap between the electronic states described by the QM method and the classical MM force field, leading to unphysical forces. Incorrect handling of long-range electrostatics across the QM/MM boundary is a frequent culprit.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify the charge neutrality of the entire QM region and the interface treatment.

- Check for overlapping van der Waals parameters or incorrectly assigned atom types at the boundary.

- Examine the SCF (Self-Consistent Field) convergence in the QM region at the divergent step—non-convergence can produce garbage forces.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the choice of QM method (e.g., DFT functional) for compatibility with the MM region. Implement a consistent electrostatic potential-matching scheme. Apply a distance-dependent dielectric constant or explicit solvent screening at the boundary. Reduce the initial optimization step size.

Issue 3: Convergence to an Unphysical Saddle Point or High-Energy State

- Symptoms: Optimization converges (forces fall below threshold), but the resulting geometry has unexpected bond lengths, angles, or clearly distorted electronic density.

- Root Cause: The optimizer is trapped by a discontinuity in the potential energy surface (PES). This can happen if different electronic states (e.g., singlet vs. triplet) are close in energy and the calculation jumps between them.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Perform a frequency calculation on the optimized structure; the presence of large imaginary frequencies indicates a saddle point.

- Analyze the spin density or orbital occupations in the QM region for unexpected patterns.

- Manually perturb the converged geometry slightly and re-optimize to see if it falls to a lower energy state.

- Solution: Use stricter SCF convergence criteria. Employ a different optimization algorithm (e.g., transition state methods if looking for a saddle, but minimum-seekers like L-BFGS for stable structures). Apply constraints to key reaction coordinates in initial stages. Consider using a metadynamics or simulated annealing approach to escape local minima.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose the optimal size for the QM region to avoid boundary artifacts? A: There is no universal rule, but a systematic approach is required. Start with a minimal QM region and gradually increase its size (e.g., by adding concentric layers of residues or functional groups). Plot the key energy of interest (e.g., reaction energy, activation barrier) against QM region size. The optimal region is where this value plateaus, indicating boundary effects are minimized. Always include complete chemical moieties and consider the range of electrostatic and polarization effects.

Q2: What are the best practices for treating the QM/MM boundary when covalent bonds are cut? A: The most common method is the use of link atoms (usually hydrogen) to satisfy the valency of the QM region. However, this introduces artificial degrees of freedom. Best practices include: 1) Placing the boundary on a single C-C bond where possible, as they are less polar. 2) Using a charge-shifting scheme (like the "shift" model) to redistribute charge from the link atom. 3) Applying constraints or specialized potentials (like the "connection atom" method) to prevent the link atom from distorting the geometry. Always test the boundary treatment on a known benchmark system.

Q3: My QM/MM simulation oscillates with one software but converges with another, using the same parameters. Why? A: Different software packages implement QM/MM coupling, boundary conditions, and optimization algorithms differently. Key differences include: the handling of long-range electrostatics (Ewald vs. cutoff), the exact formulation of the MM point-charge force on the QM Hamiltonian, and the numerical gradients' precision. Check the documentation for specifics on electrostatic embedding, link atom treatment, and the optimizer's tolerance settings. Replicate the working software's protocol as closely as possible.

Q4: How can I diagnose if oscillations are due to the QM solver vs. the MM force field? A: Perform a controlled isolation test. First, freeze all MM atoms and run a pure QM optimization on the QM region alone. If oscillations persist, the issue is in the QM method/parameters (SCF convergence, basis set, functional). If it converges, the problem is in the coupling. Next, run a pure MM minimization of the full system (treating the QM region with MM parameters). Oscillations here point to an MM force field issue (e.g., bad parameters at the boundary). Convergence here but failure in the coupled run confirms a QM/MM interface problem.

Table 1: Common QM/MM Boundary Schemes and Their Stability Profile

| Scheme | Description | Force Continuity? | Common Artifacts | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Embedding | QM region calculated in vacuum, coupled via bonds only. | High | Large electrostatic errors | Non-polar, gas-phase like active sites |

| Electrostatic Embedding | MM point charges included in QM Hamiltonian. | Moderate (discontinuities at cutoff) | Charge spill-out, polarization errors | General use, especially for charged/polar reactions |

| Link Atom with Capping | Covalent bond cut, capped with H; charge redistributed. | Low (if not carefully treated) | Over-polarization, structural distortion | Covalent boundaries where necessary |

| Pseudopotential / LOC | Uses a frozen hybrid orbital at boundary. | High | Complex setup, parameter dependence | Robust production simulations for large systems |

Table 2: Optimization Algorithm Performance for Problematic QM/MM Surfaces

| Algorithm | Type | Tolerance for Discontinuities | Convergence Speed | Risk of Divergence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent | Gradient-based | Very Low | Slow (initial steps) | High | Low |

| Conjugate Gradient | Gradient-based | Low | Moderate | Medium | |

| L-BFGS | Quasi-Newton | Medium | Fast (near minimum) | Low | |

| FIRE | Dynamics-based | High | Fast (rough landscape) | Very Low | |

| Berny (TS) | Hessian-based | Very Low | Varies | High (if poor Hessian) |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Diagnosis of QM/MM Oscillations

Objective: To isolate the root cause (QM, MM, or Interface) of energy oscillations in a QM/MM optimization.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Methodology:

- Initial Failed Trajectory Analysis: From the oscillating/diverging QM/MM run, extract the geometry from the step before the first major energy spike. Use this as the starting structure X0 for all subsequent diagnostic steps.

- Pure QM Stability Test:

- Create a subsystem consisting only of the atoms defined as the QM region in the original simulation.

- Apply the exact same QM method, basis set, and convergence criteria.

- Using X0 coordinates, perform a single-point energy calculation twice in succession. Record any difference in energy (>0.1 kcal/mol indicates SCF instability).

- Run a geometry optimization of this isolated QM region, starting from X0. Plot energy vs. step.

- Pure MM Stability Test:

- Assign MM force field parameters to all atoms, including the original QM region.

- Using the full X0 system, run an MM energy minimization with very tight convergence (gradient tolerance 0.001 kcal/mol/Å). Monitor energy.

- Partial QM/MM Test (Reduced Coupling):

- Re-run the original QM/MM simulation, but remove the electrostatic embedding (i.e., mechanical embedding only). Optimize from X0.

- If stable, the issue is electrostatic coupling. If unstable, the issue is likely mechanical/ bonded coupling at the boundary.

- Boundary Proximity Analysis:

- From the oscillating trajectory, calculate the distance of every atom to the QM/MM boundary for each step.

- Correlate distance changes > 0.1 Å with changes in atomic force vector direction or magnitude.

- Solution Implementation & Validation: Based on the diagnosed cause (e.g., SCF instability, bad electrostatic cutoff), apply the corrective solution from the Troubleshooting Guide. Re-optimize from X0 and confirm stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for QM/MM Diagnostics

| Item / Software | Category | Primary Function in Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian, ORCA, PSI4 | QM Engine | Provides the quantum mechanical energy and forces; critical for testing SCF stability and method suitability. |

| AMBER, CHARMM, OpenMM | MM Engine | Provides the classical force field energy and forces; used to validate the MM region's parameterization. |

| CP2K, Q-Chem | Integrated QM/MM | Packages with robust QM/MM implementations; useful for comparing different boundary treatments. |

| PyMOL, VMD | Visualization | Essential for visually inspecting geometries, boundary atoms, and structural distortions during oscillation. |

| Jupyter Notebooks | Analysis Environment | For scripting custom analysis of energy/force trajectories, distance monitoring, and plotting diagnostics. |

| Numerical Gradient Checker | Validation Script | A custom or package-provided tool to verify the consistency of analytical forces by comparing to finite-difference approximations. |

Diagnostic Workflow Diagrams

Title: Root Cause Isolation Workflow for QM/MM Failures

Title: Force Coupling and Discontinuity at QM/MM Boundary

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Convergence in QM/MM Optimizations

FAQ 1: My QM/MM geometry optimization stalls or oscillates without reaching convergence. Could my choice of QM method be the cause? Yes. High-level ab initio methods (e.g., CCSD(T)) and Density Functional Theory (DFT) functionals provide high accuracy but have very complex, non-linear potential energy surfaces (PES). This can lead to numerous shallow minima, causing oscillations. Semi-empirical methods (e.g., PM6, DFTB) have smoother, parameterized PES, which often converge faster but may be trapped in incorrect minima due to lower accuracy. The mismatch between the precision of the QM method and the MM force field can also create artificial forces at the boundary, hindering convergence.

FAQ 2: When should I switch from a semi-empirical to a high-level QM method during a QM/MM protocol to improve convergence? Start with a semi-empirical method for initial, large-scale conformational sampling and rough optimization. Once the system is near a minimum, switch to a higher-level method for final refinement. This two-step protocol leverages the fast convergence of semi-empirical methods for the early stages and the accuracy of high-level methods at the end. Implement this using an "ONIOM-like" layered approach within your software.

FAQ 3: How do I adjust optimization algorithms based on my QM method choice? Use algorithm settings appropriate for the method's PES characteristics.

| QM Method Tier | Recommended Algorithm | Key Rationale | Typical Max Step |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Level (DFT, ab initio) | Rational Function Optimization (RFO) or GDIIS | Better handling of anharmonic, complex PES near minima. | 0.01 – 0.03 Å/rad |

| Semi-Empirical (PMx, DFTB) | Berkeley Algorithm or Standard Quasi-Newton | Efficient for smoother, parabolic PES. | 0.05 – 0.10 Å/rad |

| Mixed (High QM/MM) | Conservative (Trust-Radius) RFO | Mitigates noise from QM-MM boundary. | 0.015 – 0.025 Å/rad |

Experimental Protocol: Two-Stage QM/MM Optimization for Problematic Systems

- Objective: Achieve stable convergence for a drug-enzyme transition state.

- Stage 1 (Semi-Empirical Pre-Optimization):

- System Setup: QM region (~50 atoms) treated with PM6-D3H4. MM region with AMBER ff14SB.

- Optimization: Use a quasi-Newton algorithm (e.g., L-BFGS). Set maximum step size to 0.08 Å, convergence criteria to "loose" (energy change < 1.0e-4 Hartree, gradient < 1.0e-2 Hartree/Å).

- Check: Monitor root-mean-square (RMS) gradient. Proceed if stable decrease over 50 cycles.

- Stage 2 (High-Level Refinement):

- Method Switch: Change QM method to ωB97X-D/6-31G(d). Keep MM force field identical.

- Optimization: Switch to RFO algorithm. Tighten convergence (gradient < 4.5e-4 Hartree/Å). Reduce max step to 0.02 Å.

- Validation: Confirm vibrational frequency analysis yields exactly one imaginary frequency for the transition state.

Troubleshooting Guide: "Convergence Oscillations" Error

- Symptom: Energy and gradient values cycle between 2-3 values without improving.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Check the QM/MM boundary. Ensure no sensitive bonds (e.g., breaking/forming) are cut. Use a link atom scheme correctly.

- Visualize the steps. The oscillation often indicates "sloshing" of a group (like a solvent molecule) between two positions.

- Solutions:

- For High-Level QM: Significantly reduce the trust radius (max step) by 50%. Switch to a more robust algorithm (e.g., from quasi-Newton to GDIIS).

- For Semi-Empirical QM: Tighten the SCF convergence criteria (by 1-2 orders of magnitude) to reduce numerical noise in gradients. Consider applying harmonic restraints (5-10 kcal/mol/Ų) to mobile MM solvent atoms near the QM region.

- Universal: Freeze atoms >10 Å from the QM region, re-optimize, then slowly release them.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: QM Method Selection Flowchart for Convergence

Diagram Title: Two-Stage QM/MM Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Category | Example(s) | Function in QM/MM Convergence Studies |

|---|---|---|

| High-Level QM Software | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem | Provides robust ab initio/DFT engines with advanced optimization algorithms (GDIIS, RFO) critical for final convergence. |

| Semi-Empirical & MD Package | AMBER, GROMACS + DFTB/PMx plugins | Enables efficient semi-empirical pre-optimization and force field parameterization for the MM region. |

| Hybrid Interface | ChemShell, QSite, ONIOM (Gaussian) | Manages QM/MM partitioning, boundary handling, and coordinated multi-stage optimization protocols. |

| Geometry Analysis Tool | Pymol, VMD, CYLview | Visualizes optimization steps to diagnose oscillating atoms or problematic boundary conditions. |

| Benchmark Dataset | S66, JSCH-2005, DrugBank fragments | Provides standardized systems for testing method performance and convergence behavior. |

| Link Atom Capping Scheme | Hydrogen Link Atoms, Generalized Hybrid Orbital (GHO) | Mitigates artifacts at the QM/MM boundary that can cause convergence failure. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our QM/MM geometry optimization fails to converge, with large forces reported on atoms at the QM/MM boundary. What is the most likely cause and how can we fix it? A: This is a classic symptom of improper initial molecular mechanics (MM) minimization. Large steric clashes or unrealistic bond lengths/angles in the starting structure create extreme forces that the QM/MM optimizer cannot resolve.

- Solution Protocol:

- Isolate and Minimize: Perform a thorough, classical MM-only minimization on the entire system (solvent, protein, ligand) before defining the QM region.

- Use Strong Restraints: Apply strong positional restraints (e.g., 500 kcal/mol/Ų) on protein backbone atoms and the ligand's heavy atoms.

- Gradual Relaxation: Follow with a series of minimizations, gradually reducing the restraint force constant (e.g., 100, 10, 1 kcal/mol/Ų) to allow the system to relax without deviating from the experimental starting fold.

- Proceed to QM/MM: Only after the MM system is stable (RMSD gradient < 0.1 kcal/mol/Ų) should you define the QM region and begin QM/MM optimization.

Q2: How do incorrect protonation states lead to convergence issues in enzyme mechanism simulations? A: Incorrect protonation states of active site residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, His, Lys) can create unrealistic electrostatic potentials and hydrogen-bonding networks. This forces the QM region to optimize to a high-energy, non-physical geometry, often resulting in convergence failure or a misleading mechanistic pathway.

- Solution Protocol:

- Perform pKa Calculations: Use empirical methods (e.g., PROPKA) or more advanced constant-pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) simulations to predict residue pKa values at your specific simulation pH.

- Manual Inspection: Visually inspect the active site hydrogen-bonding network. Use molecular graphics software (e.g., PyMOL, VMD) to add/remove protons to optimize this network.

- Test Alternatives: For ambiguous residues like Histidine (HID, HIE, HIP), run parallel QM/MM minimizations with different protonation states. The correct state typically converges faster and to a lower energy.

Q3: Our QM/MM energy shows an abrupt, unphysical jump during optimization. What should we check? A: This often indicates a "hot" atom due to a missing or incorrectly placed hydrogen atom, or a drastic change in the MM point-charge field felt by the QM atoms.

- Troubleshooting Checklist:

- Hydrogen Placement: Verify all polar hydrogens, especially on titratable residues and water molecules near the QM region, are correctly added and oriented.

- Link Atom Consistency: Ensure the treatment of the QM/MM boundary (link atom scheme, charge redistribution) is consistent and that no bonded terms are accidentally counted twice.

- Charge Shuffling: If using a electrostatic embedding scheme, monitor the MM point charges. A sudden shift in a nearby charged side chain (e.g., Arg, Asp) can cause this jump.

Table 1: Impact of MM Pre-Minimization on QM/MM Optimization Convergence

| System (Enzyme-Ligand) | No MM Minimization | 3-Stage Restrained MM Minimization | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 Protease | Failed after 150 cycles | Converged in 45 cycles | Stable active site geometry |

| Cytochrome P450 | Large boundary forces (>0.5 a.u.) | Minimal boundary forces (<0.05 a.u.) | Successful spin state calculation |

| Beta-Lactamase | Unphysical hydrogen transfer | Physiologically plausible intermediate | Correct mechanistic inference |

Table 2: Convergence Outcomes for Different Histidine Protonation States in a Catalytic Triad

| Residue (Protonation) | QM/MM Steps to Converge | Final RMSD (Å) | Relative Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| His-159 (HID - δ protonated) | 32 | 0.12 | 0.0 (Reference) |

| His-159 (HIE - ε protonated) | 78 | 0.45 | +8.7 |

| His-159 (HIP - doubly protonated) | Failed to converge | N/A | N/A |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Robust System Preparation for QM/MM Studies

- Initial Structure: Obtain PDB file. Remove crystallographic co-solvents. Add missing side chains (e.g., using Modeller).

- Protonation Assignment: Run PROPKA to estimate pKa values. Manually adjust states in molecular visualization software, focusing on the active site. Add all hydrogen atoms.

- Solvation & Neutralization: Place the system in a TIP3P water box (≥10 Å padding). Add counterions (Na+/Cl-) to neutralize system charge.

- Restrained MM Minimization: Using AMBER/CHARMM/OpenMM, perform:

- Step 1: Minimize only hydrogens (500 steps).

- Step 2: Minimize water and ions with solute restrained (force constant 10 kcal/mol/Ų, 2500 steps).

- Step 3: Full system minimization with gradual restraint release on protein backbone (from 5 to 0.1 kcal/mol/Ų over 5000 steps).

- System Validation: Check for remaining clashes, reasonable bond lengths, and stable hydrogen bonds in the active site.

Protocol B: pKa Prediction for Active Site Residues

- Input Preparation: Use the pre-minimized, hydrogenated structure from Protocol A, Step 4.

- Empirical Calculation: Execute PROPKA (e.g., via

pdb2pqror standalone) at the target simulation pH (typically 7.0). - Analysis: Examine the output file. Residues with a predicted pKa ±1.5 pH units from the solvent pH are candidates for alternate protonation.

- Comparative MD: For critical residues, set up multiple short (5-10 ns) MM MD simulations with different protonation states. Analyze stability (RMSD) and hydrogen-bond occupancy to select the most plausible state.

Visualizations

Title: QM/MM System Preparation Workflow

Title: Troubleshooting Flow for QM/MM Convergence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Software | Function in QM/MM System Prep |

|---|---|

| PROPKA | Empirical tool for predicting protein residue pKa values to guide protonation state assignment. |

| PDB2PQR | Automated pipeline for adding hydrogens, assigning charge states, and generating format files for simulations. |

| AmberTools / CHARMM-GUI | Suites for adding solvent, ions, and performing critical restrained MM minimization stages. |

| Gaussian, ORCA, or CP2K | QM software packages used for the quantum region energy and force calculations within QM/MM. |

| PyMOL or VMD | Molecular visualization software for manually inspecting and correcting hydrogen bonding networks and protonation. |

| CpHMD Modules (AMBER/CHARMM) | For advanced, dynamics-based constant-pH simulations to determine protonation states. |

| Link Atom Patches | Specialized parameters/residue definitions to correctly handle covalent bonds cut by the QM/MM boundary. |

Building for Success: Proven Methodological Setups for Stable QM/MM Optimizations

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My QM/MM geometry optimization fails to converge. How can I modify my QM region to resolve this? A1: Convergence failure often stems from an unstable QM region boundary. If the QM region contains highly charged or reactive residues (e.g., a dissociating acid or base) near the MM boundary, electrostatic interactions can cause oscillations. First, try expanding the QM region to include the complete side chain of any charged residue or the entire backbone of a residue involved in bond-breaking/forming. If the system is too large for this, consider using a capping hydrogen at the boundary, but ensure its position is constrained initially. Switching the QM method to a more robust but lower-level theory (e.g., from DFT to HF) for initial optimization steps can also help achieve convergence before refining with a higher-level method.

Q2: How do I choose between mechanical and electronic embedding for my charged QM region? A2: The choice is critical for stability. Use electronic embedding when the QM region's electrostatic properties are polarized by the MM environment (e.g., enzyme active sites). It is more accurate but can cause convergence issues if the QM/MM boundary cuts across polar bonds. Use mechanical embedding only for neutral QM regions where electrostatic polarization is negligible, as it treats MM point charges classically. For charged systems, mechanical embedding is generally not recommended as it leads to significant errors. A hybrid approach is often used: treat the immediate solvation shell or key ionic pairs within the QM region.

Q3: I am getting unphysical distortions in the QM region during optimization. What's wrong? A3: This is a classic sign of an improperly defined QM region cutting through a chemical bond. The link atom scheme, while common, can introduce artificial forces. Ensure the cut is made across a single (C-C) bond where possible, not near a functional group. Use a consistent and validated link atom scheme (e.g., hydrogen link atoms). Check the charge and spin state of the total QM region; an incorrect assignment is a major source of distortion. Perform a single-point energy calculation on the initial structure to check for an abnormally high energy, which indicates an unstable starting configuration.

Q4: How large should my QM region be to ensure accuracy without prohibitive cost? A4: There is no universal size, but systematic testing is required. The table below summarizes the trade-offs based on current research:

Table 1: QM Region Size vs. Performance Characteristics

| QM Region Size (Atoms) | Typical Accuracy (ΔE kcal/mol) | Relative Computational Cost | Convergence Stability | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 50 | High (> 5) | Low | Low | Initial testing, gas-phase models |

| 50 - 150 | Medium (2-5) | Moderate | Medium | Standard enzyme active sites |

| 150 - 300 | Low (1-2) | High | High | Multiple substrate residues, metal clusters |

| > 300 | Very Low (<1) | Very High | Very High | Large cofactors, membrane protein pores |

Note: ΔE is an approximate error relative to a benchmark (e.g., full QM) for reaction energies. Actual values depend on system and method.

Experimental Protocol for Determining Optimal QM Region Size

- Objective: To find the smallest QM region that yields energies within 1 kcal/mol of a reference "large" QM region.

- Procedure:

- Define a Reference: Perform a single-point energy calculation on your optimized structure using a large, chemically intuitive QM region (e.g., entire substrate + all residues within 5Å). This is your reference energy, Eref.

- Create Progressive Shells: Generate a series of QM regions by systematically adding concentric shells of residues/water molecules around the reaction center.

- Single-Point Calculations: For each QM region size, perform a single-point energy calculation using the same coordinates and QM method.

- Analyze Convergence: Plot the energy difference (Etest - E_ref) against QM region size. The point where the difference plateaus within your target threshold (e.g., 1 kcal/mol) defines your optimal size.

- Test Optimization Stability: Use the candidate region(s) from step 4 to perform a full QM/MM geometry optimization. Monitor SCF and geometry convergence steps.

Mandatory Visualization

Title: QM Region Selection and Testing Workflow

Q5: What are the best practices for handling protonation states at the QM/MM boundary? A5: Incorrect protonation states are a major source of instability. Follow this protocol:

- Perform a classical MD simulation with explicit solvent at the desired pH to sample stable protonation states of all residues.

- Use a continuum electrostatics tool (e.g., PROPKA) on the average structure to predict pKa values of residues within and near the proposed QM region.

- For residues within the QM region, assign the protonation state that is dominant at the simulation pH. Manually adjust for known catalytic states.

- For residues cut at the boundary, the MM side must have its charge group adjusted to neutralize the link atom. Use library charge values that are consistent with your force field.

- Always test the sensitivity of your results by running key calculations with an alternative, plausible protonation state.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software & Computational Tools for QM/MM Setup

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cpptraj | Analysis | Process MD trajectories to identify stable residue conformations for QM region selection. | Use to calculate RMSD and distance matrices. |

| PROPKA | Pre-processing | Predict pKa values of protein residues to assign correct protonation states. | Critical for enzymatic systems; results can be sensitive to local environment. |

| CHARMM/ AMBER/ GROMACS | MD Engine | Generate equilibrated structures and perform classical simulations for system preparation. | Ensure compatibility of force field parameters with your chosen QM/MM software. |

| Gaussian, ORCA, TeraChem | QM Engine | Perform the quantum mechanical calculations within the QM region. | Balance between method accuracy (DFT functional) and computational cost for your system size. |

| Chemcraft/ VMD | Visualization | Visually inspect QM/MM boundaries, link atom placements, and geometric distortions. | Essential for diagnosing unphysical structures post-optimization. |

| QSite, QChem | Integrated QM/MM | Specialized packages for combined QM/MM calculations with built-in embedding schemes. | Often have more robust handling of boundary issues than interfaced separate codes. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Convergence in QM/MM Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My QM/MM geometry optimization oscillates and fails to converge. Which embedding scheme should I investigate first? A: This is often a sign of an electrostatic boundary problem. Start by verifying your Mechanical Embedding (ME) setup. Ensure the QM region is sufficiently large to encompass all significant electronic rearrangements. If oscillations persist, switch to Electronic Embedding (EE), which includes the MM point charges in the QM Hamiltonian, providing a more consistent field. ME is simplest but can cause convergence issues at the QM/MM boundary due to abrupt changes in the electrostatic potential.

Q2: When using Electronic Embedding (EE), I encounter charge spill-out or overpolarization artifacts. How can I resolve this? A: Charge spill-out occurs when the electron density of the QM region excessively polarizes towards nearby MM point charges. Implement a charge-shifting or charge-scaling protocol for MM atoms within a buffer zone (typically 2-4 Å) of the QM region. Alternatively, transition to Polarized Embedding (PE), which uses polarizable force fields to allow MM atoms to respond to the QM electron density, mitigating this unphysical overpolarization.

Q3: My Polarized Embedding (PE) calculation is computationally expensive and converges slowly. Are there practical steps to improve performance? A: Yes. First, limit the polarizable region to the immediate vicinity of the QM zone (e.g., 8-12 Å). Use a classical Drude oscillator or induced dipole model with a tighter convergence threshold for the polarization loop (e.g., 10^-6 D) within each SCF cycle. Employ a two-layer PE model where only the first solvation shell is polarizable. Ensure your software uses an efficient iterative solver (e.g., Conjugate Gradient) for the coupled polarization equations.

Q4: For drug binding energy calculations, which scheme offers the best trade-off between convergence stability and accuracy? A: For binding energies, convergence of the free energy landscape is critical. Electronic Embedding (EE) is the recommended baseline, as it captures essential electrostatic interactions like hydrogen bonding and salt bridges without the full cost of PE. Studies show EE typically converges binding energies to within 2-4 kcal/mol of more advanced methods, with more stable optimization paths than ME. PE should be reserved for systems with strong, specific polarization effects (e.g., metal ions, halogen bonds).

Q5: How do I diagnose if my convergence failure is due to the embedding scheme versus other issues (e.g., basis set, SCF convergence)? A: Follow this diagnostic protocol:

- Isolate the SCF: Run a single-point energy with a large SCF max cycle count on the problematic geometry. If the SCF fails, the issue is electronic, not the embedding.

- Test Mechanical First: Run a brief optimization using ME with a frozen MM region. If it converges, the issue is likely in the electrostatic coupling.

- Benchmark with a Smaller System: Create a minimal model (e.g., just the active site and key residues). If EE/PE converges on the small system but not the large one, the problem is likely electrostatic mismatch at the boundary.

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Convergence Metrics for Different Embedding Schemes in Model System (Water Cluster)

| Embedding Scheme | Avg. Optimization Steps to Converge (ΔE < 1e-5 a.u.) | Avg. SCF Cycles per Step | Relative Energy Error (kcal/mol)* | Typical Artifact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical (ME) | 45 ± 12 | 18 | 5.0 - 10.0 | Boundary discontinuity, forced oscillations |

| Electronic (EE) | 28 ± 8 | 22 | 1.0 - 3.0 | Charge spill-out, overpolarization |

| Polarized (PE) | 65 ± 20 | 35 (includes pol. loop) | 0.5 - 1.5 | Slow polarization loop convergence |

*Error relative to a full QM reference calculation.

Table 2: Application-Specific Recommendations for Stable Convergence

| Research Goal (System Example) | Recommended Scheme | Key Convergence Tuning Parameter | Expected Stability Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Ground-State Geometry (Ribosome) | Electronic Embedding (EE) | Charge-shielding radius (1.5-2.0 Å) | Stable, avoids boundary-induced oscillations. |

| Reaction Pathway (Enzyme Catalysis) | Electronic Embedding (EE) | QM region size (+1-2 residue buffer) | Smooth potential energy surface for TS location. |

| Spectroscopic Property (Chromophore in Protein) | Polarized Embedding (PE) | Polarizable region cutoff (10-12 Å) | Accurate excited states; pol. loop must be tight. |

| High-Throughput Ligand Screening | Mechanical Embedding (ME) | Tight MM restraint on QM/MM atoms | Fast, but requires careful validation for each scaffold. |

Experimental Protocols for Convergence Testing

Protocol 1: Baseline Convergence Test for a New QM/MM System

- Preparation: Prepare the hybrid structure with protonation states assigned. Define the initial QM region.

- Mechanical Embedding Run: Perform a geometry optimization using ME (MM point charges not seen in QM Hamiltonian). Use standard thresholds (e.g., gradient < 0.001 a.u.).

- Monitor: Record the number of steps, energy oscillation pattern, and final root-mean-square (RMS) gradient.

- Switch to Electronic Embedding: Using the last geometry from (2), restart optimization with EE.

- Comparison: Compare the optimization history plots. EE should show a smoother, monotonic convergence profile. A significant reduction in steps (>30%) indicates ME was causing boundary issues.

Protocol 2: Diagnosing and Mitigating Overpolarization in EE/PE

- Symptom Identification: Check for abnormally large dipole moments in the QM region or distorted geometry towards MM point charges.

- Charge Tuning: Redefine the MM region charges within 3.0 Å of the QM zone using a scaling factor (e.g., 0.5) or a charge shift model (e.g., charge redistribution to adjacent atoms).

- Restart Optimization: Re-optimize from an earlier step (before distortion) with the tuned charges.

- Validation: Perform a single-point energy calculation with a larger QM region or a higher theory level on the final geometry to assess stability.

Visualization of Method Relationships and Workflows

Title: QM/MM Embedding Convergence Troubleshooting Decision Tree

Title: Electrostatic Coupling in QM/MM Embedding Schemes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Parameters for Convergence Studies

| Item | Function in Convergence Studies | Recommended Setting/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem) | Performs the QM calculation; its SCF solver stability is foundational. | Use "SCF=Tight" and "NoSymm" to avoid symmetry-related convergence issues. |

| QM/MM Interface Software (e.g., Amber-TeraChem, QSite, CP2K) | Manages partitioning, embedding, and force coupling. | Ensure consistent atom numbering and charge model (e.g., RESP charges) between MM and QM. |

| Polarizable Force Field (e.g., AMOEBA, Drude) | Provides the polarizable environment for PE calculations. | For Drude oscillators, use a high spring constant (e.g., 1000 kcal/mol/Ų) to prevent "polarization collapse." |

| Charge-Shielding Scripts (Custom Python/MATLAB) | Modifies MM point charges near the QM boundary to prevent overpolarization. | Implement a Fermi-type switching function: q_scaled = q / (1 + exp(-k*(r-r0))) |

| Geometry Analysis Tool (e.g., VMD, PyMOL, cpptraj) | Visualizes optimization pathways to identify oscillating atoms or bonds. | Plot RMSD vs. optimization step for the QM region to visually diagnose instability. |

| Convergence Accelerator (e.g., EDIIS, CDIIS for SCF) | Improves and stabilizes SCF convergence in the presence of external MM charges. | Always enable DIIS for SCF acceleration in EE and PE calculations. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My QM/MM geometry optimization is oscillating and failing to converge. What are the primary causes? A: This is a classic convergence issue. The primary causes are: 1) An overly large QM region leading to expensive, noisy gradients, 2) Incompatible or unbalanced force field parameters (MM) with the QM method at the boundary, 3) An insufficiently tight SCF convergence criterion in the QM calculation propagating noise into the optimization, and 4) The use of an inappropriate optimization algorithm (e.g., steepest descent) for a complex, rough energy landscape. First, ensure your QM SCF convergence is tight (1.0e-7 a.u. or better). Consider reducing the QM region size or using a mechanical embedding scheme for initial rough optimization before switching to electrostatic embedding.

Q2: I encounter "bond formation" errors or steric clashes at the QM/MM boundary when preparing my system. How can I avoid this?

A: This typically arises from improper hydrogen capping of the QM region. Follow this protocol: 1) Identify the cut bond. 2) Remove the MM atom, leaving the QM atom with a dangling bond. 3) Cap the QM atom with a hydrogen atom. 4) The hydrogen's position must be calculated precisely: place it along the original bond vector with a standard bond length (e.g., 1.09 Å for C-H). Many pre-processing tools (e.g., pdb2gmx with CHARMM, tleap with AMBER, or specialized scripts like moltemplate) can automate this, but manual verification is critical.

Q3: During optimization, my protein backbone near the QM region is becoming distorted. What is the likely fix? A: This suggests insufficient restraint on the MM region. Apply positional restraints to protein backbone atoms beyond a certain radius (e.g., 10-15 Å) from the QM region's center. Use harmonic restraints with a force constant of 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm². This "freezes" the bulk protein while allowing the active site and nearby side chains to relax, preventing unphysical drift and focusing computational effort on the chemically relevant region.

Q4: My hybrid optimization (e.g., using ONIOM) is extremely slow. What steps can improve performance? A: Performance bottlenecks often lie in QM gradient calculation. Implement the following: 1) Use a smaller QM method/basis set for initial micro-iterations (e.g., PM6/DFTB for MM, then B3LYP/6-31G* for final refinement). 2) Utilize linear-scaling or approximated QM methods if available. 3) Ensure efficient parallelization; QM codes often parallelize over basis functions, while MM codes parallelize over atoms. Balance the workload. 4) Consider micro-iterative optimization techniques that freeze the MM region for several QM steps.

Q5: How do I verify that my optimized QM/MM structure is chemically sensible and not stuck in a local minimum? A: Conduct a multi-pronged validation: 1) Geometry Checks: Bond lengths and angles in the QM region should match known values from high-level QM calculations or crystal structures of small model compounds. 2) Energy Monitoring: Plot the total energy and max gradient vs. optimization step. The gradient should decrease monotonically to your threshold. 3) Comparative Optimization: Restart the optimization from the final structure with a different algorithm (e.g., from conjugate gradient to limited-memory BFGS). 4) Hessian Calculation: Perform a frequency calculation on a small model system to ensure no imaginary frequencies correspond to the reaction coordinate of interest.

Table 1: Comparison of Optimization Algorithms for QM/MM Convergence

| Algorithm | Convergence Speed (Avg. Steps) | Stability (Likelihood of Oscillation) | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent | Very Slow (>1000) | High (Poor) | Only for initial steps from severely clashed structures |

| Conjugate Gradient | Moderate (300-600) | Medium | Medium-sized systems with smooth gradients |

| L-BFGS | Fast (100-300) | High (Good) | Default choice for most QM/MM geometry optimizations |

| Truncated Newton | Varies (50-200) | High | When precise Hessian information is calculable (small QM) |

Table 2: Typical QM SCF Convergence Settings for Stable Gradients

| QM Method | Initial SCF Tolerance (a.u.) | Final/Tight SCF Tolerance (a.u.) | Max SCF Cycles | Impact on Gradient Noise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-empirical (PM6) | 1.0e-5 | 1.0e-7 | 200 | Low (Use tight from start) |

| Density Functional (B3LYP) | 1.0e-6 | 1.0e-8 | 300 | Critical - Loose tolerance causes major noise |

| Hartree-Fock | 1.0e-5 | 1.0e-7 | 400 | High - Tight convergence essential |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: System Preparation for Enzyme QM/MM Study

- Initial Structure: Obtain protein-ligand complex from PDB (e.g., 1OG5). Remove crystallographic waters and ions not in the active site.

- Parameterization: Use

tleap(AMBER) orpdb2gmx(GROMACS) to assign MM force fields (FF14SB for protein, GAFF2 for ligand). Generate ligand parameters usingantechamber(AMBER) orCGenFF(CHARMM). - QM Region Selection: Using VMD or Chimera, select all residues and ligands within 5Å of the catalytic center. Refine to include only essential groups (e.g., substrate, key amino acid side chains, catalytic metals). A typical QM region contains 50-150 atoms.

- Hydrogen Capping: For each bond cut between QM and MM atoms, delete the MM atom and add a hydrogen capping atom to the QM atom using the

bondandangleinformation from the force field to set the geometry. - Solvation & Neutralization: Solvate the system in a TIP3P water box with 10Å padding. Add Na⁺/Cl⁻ ions to neutralize charge and achieve 0.15M concentration.

- Restraints Preparation: Define positional restraint groups: Strong Restraints (force constant 1000 kJ/mol/nm²) for protein backbone >12Å from QM center. Weak Restraints (500 kJ/mol/nm²) for protein side chains 5-12Å from QM center.

Protocol: Two-Stage QM/MM Optimization Workflow

- Stage 1: MM Pre-relaxation.

- Goal: Remove steric clashes.

- Method: Perform 5000 steps of steepest descent energy minimization on the entire system, with all restraints active.

- Convergence Criteria: Maximum force < 1000 kJ/mol/nm.

- Stage 2: Hybrid QM/MM Optimization.

- Goal: Achieve a chemically optimized active site.

- QM Setup: Define QM region, method (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G*), and charge/multiplicity. Set SCF convergence to 1.0e-8 a.u.

- MM Setup: Apply electrostatic embedding. Use the assigned MM force field.

- Optimization: Run L-BFGS optimization with the following convergence criteria: Energy change < 1.0e-6 Hartree, Max force < 4.5e-4 Hartree/Bohr, RMS force < 3.0e-4 Hartree/Bohr.

- Validation: Calculate single-point energy on final structure with a higher QM method (e.g., ωB97XD/def2-TZVP). Compare key geometry metrics to benchmark data.

Diagrams

Title: QM/MM Optimization Workflow Diagram

Title: Convergence Failure Troubleshooting Logic Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Toolkits for QM/MM Optimization

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MM MD Engine | High-performance simulation, pre-relaxation, force field assignment. | Excellent for MM prep; requires interface (e.g., gmx-qmmm) for QM/MM. |

| AMBER (sander, pmemd) | Hybrid MD Engine | Integrated QM/MM (SQM, DFTB, external QM) within a robust MD suite. | Native support for many QM methods; sander can be slower than pmemd. |

| Gaussian/ORCA | QM Engine | Provides high-accuracy QM energy and gradients for the QM region. | Called externally by MD engine. ORCA is free for academics and highly efficient. |

| CP2K | Ab Initio MD | Performs QM and QM/MM calculations with excellent scalability for plane-wave DFT. | Best for periodic systems and advanced DFT functionals. |

| CHARMM | Hybrid MD Engine | Pioneering QM/MM code with extensive force fields and scripting. | Steep learning curve but extremely flexible for method development. |

| Pymol/VMD/Chimera | Visualization | Critical for QM region selection, capping verification, and result analysis. | Visual inspection of the boundary is non-negotiable for system integrity. |

| Molpro/TERACHEM | QM Engine (Specialized) | High-level ab initio (Molpro) or GPU-accelerated DFT (TERACHEM) for QM region. | Used for highest accuracy or maximum performance on GPU clusters. |

Technical Support Center

AMBER/Gaussian

Q: My QM/MM geometry optimization in AMBER (Sander) with Gaussian as the QM engine fails with "QM deriv failed in mme." What should I do?

A: This error often indicates an instability in the QM calculation. First, ensure your QM region is electrically neutral (use the charge keyword in &qmmm). If the system is charged, apply a restraining potential. Second, check the SCF convergence in Gaussian; use tighter convergence criteria (SCF=(Conver=8,MaxCycle=200)) and consider using SCF=QC for difficult cases. Third, verify your link atom setup and that the QM/MM boundary does not cut through a conjugated system.

Q: How do I improve the convergence of the QM (Gaussian) part within an AMBER minimization? A: Use the following protocol in your Gaussian route line within the AMBER input:

The XQC (quadratic convergence) algorithm is robust for difficult SCF. The UltraFine grid improves gradient accuracy. In the AMBER &qmmm namelist, reduce the initial step size: density_predictor_step=0.001 and scfconv=1.0d-8.

Experimental Protocol: Troubleshooting AMBER/Gaussian QM/MM Optimization

- System Preparation: Use

tleapto create prmtop/inpcrd files. Define QM region with&qmmmqmcut=8.0,qmmask=':1-5',qmcharge=0,qm_theory='GAUSSIAN'. - Input Configuration: In the

sanderinput file, setmaxcyc=1000,ntmin=1(steepest descent initially), anddrms=0.001. - Gaussian Settings: Embed the route line as shown above. Provide a

%oldchk=...line for a guess from a previous calculation if available. - Execution & Diagnosis: Run

sander -O -i mdin -o mdout -p prmtop -c inpcrd. If failure occurs, examine themdoutfile for the last Gaussian output captured. Address the specific SCF or integral error found.

CHARMM/ORCA

Q: During a CHARMM/ORCA QM/MM optimization, I get "ORCA finished with error" and the Hessian appears unstable. How can I fix this?

A: This typically points to issues with the QM method or the QM/MM interface. Use a more stable DFT functional (e.g., B3LYP-D3 or ωB97X-D) with a good basis set (def2-SVP). In ORCA, enable tight optimization thresholds: ! Opt TightOpt. For the MM region, ensure proper minimization with SD (steepest descent) steps before switching to ABNR. Increase the INBFRQ value in CHARMM to update the non-bond list less frequently during optimization.

Q: What are the best settings for running ORCA efficiently from CHARMM for energy gradients?

A: Use the ! Engrad keyword in your ORCA input template within CHARMM. Employ efficient parallel settings: ! PAL4 for 4 cores. For the DFT calculation, use ! RI-JON B3LYP def2-SVP def2/J D3BJ to accelerate Coulomb integrals and include dispersion correction. In CHARMM, set QMMM ORCA MODE ENERGY and ensure QMORE 0 is used to read the gradient correctly.

Experimental Protocol: Setting up CHARMM/ORCA for Stable QM/MM Optimization

- CHARMM Script Setup: After generating the system, use:

- ORCA Template File (

orca.inp): Create a file with: - Execution: Run CHARMM with

charmm < input.inp > output.log. Theqm_coords.xyzis written and read automatically. - Diagnosis: Check the

orca.logfile created in the run directory for ORCA-specific errors on SCF or geometry convergence.

GROMACS/CP2K

Q: My QM/MM simulation in GROMACS/CP2K crashes immediately with "Particle coordinate is NaN." What's wrong?

A: This is often due to an incorrect QM/MM electrostatic coupling or an overly large initial force. Use coupling-scheme = IMOMM in your CP2K &QMMM input. Ensure your QM cell (&CELL in CP2K) is large enough to encompass the entire QM density; a margin of at least 3 Å from any QM atom to the cell boundary is recommended. Also, in the GROMACS .mdp file, set integrator = md and dt = 0.001 for the initial MM equilibration before coupling to CP2K.

Q: How do I configure CP2K for faster yet reliable DFT calculations within GROMACS?

A: Use the Quickstep module with GPW (Gaussian and Plane Waves). Employ a dual Gaussian basis set (DZVP-MOLOPT-SR-GTH) with a corresponding GTH pseudopotential. Use a relative cutoff of 40-50 Ry. Enable &AUXILIARY_DENSITY_MATRIX_METHOD ADMM2 to speed up hybrid functional calculations if needed. For pure functionals, &LS_SCF can be efficient.

Experimental Protocol: GROMACS/CP2K QM/MM Minimization Workflow

- System Preparation: Prepare

topol.topandconf.grousing standard GROMACS tools. Create a CP2K input file (qm.inp). - CP2K Input Key Settings:

- GROMACS

.mdpSettings: For minimization:integrator = steep,emtol = 100.0,emstep = 0.01. SetQMMM = yes,QMMM-grps = QM_Group, andQMMM-program = CP2K. - Run: Execute

gmx mdrun -s topol.tpr -o traj.trr. GROMACS calls CP2K as a library.

Q-Chem/NAMD

Q: In a NAMD/Q-Chem simulation, the energy diverges to large negative values. What causes this?

A: This is a classic sign of "hot" atoms, often due to incorrect force scaling between QM and MM regions. Verify the qm_scale and mm_scale parameters in your NAMD configuration file. They should typically be 1.0 and 1.0 unless using a specific electrostatic embedding model. Ensure the qmbasis and qmcharge are correctly specified. Also, confirm that the Q-Chem input file (provided via qmconfig in NAMD) uses SYMMETRY = FALSE and SCF_CONVERGENCE = 8.

Q: How can I achieve SCF convergence for a metallic or dense system in Q-Chem within NAMD? A: Use a combination of algorithmic and technical fixes. In your Q-Chem input:

For very difficult cases, consider SCF_ALGORITHM = RCA-DIIS or use SMART_SOLVENT = TRUE if simulating in solution.

Experimental Protocol: NAMD/Q-Chem Energy Minimization Setup

- NAMD Configuration (

namd.conf): - Q-Chem Input Template (

qchem.in): - Execution: Run NAMD:

namd2 +p8 namd.conf > output.log. Monitor the log for Q-Chem output sections.

| Software Pair | Key SCF Convergence Threshold | Recommended Opt. Max Cycles | Typical QM/MM Electrostatic Scheme | Default Gradient Tolerance (Hartree/Bohr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER/Gaussian | SCFConver=8 (∆E ~1E-8 au) |

200 (SCF), 1000 (MM Opt) | Mechanical Embedding (Force) or Electronic Embedding | 1.0E-4 (in AMBER drms) |

| CHARMM/ORCA | TightSCF (∆E ~1E-7 au) |

250 (SCF), 1000 (MM Opt) | Electronic Embedding | 1.0E-3 (CHARMM TOLGRD) |

| GROMACS/CP2K | EPS_SCF 1.0E-6 |

300 (SCF), Steepest Descent MM | IMOMM or Gaussian blurring | 100 kJ/mol/nm (GROMACS emtol) |

| Q-Chem/NAMD | SCF_CONVERGENCE 8 (∆E ~1E-8 au) |

200 (SCF), 1000 (MM Opt) | Mechanical or Electronic Embedding (configurable) | N/A (NAMD uses steps) |

Visualization

Title: Troubleshooting Workflow for QM/MM Convergence Issues

Title: Software Interaction in a QM/MM Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Reagent | Function in QM/MM Convergence Studies |

|---|---|

| Link Atom Patches (e.g., H-Link) | Caps severed covalent bonds at the QM/MM boundary, preventing unphysical dangling bonds in the QM region. |

| Pseudopotentials/Basis Sets (e.g., GTH, def2-SVP) | Defines the quantum mechanical wavefunction for core/valence electrons, balancing accuracy and computational cost. |

| Constraining Potentials (Harmonic Restraints) | Restrains atoms in the MM region (or distant QM atoms) to prevent large, unphysical motions that destabilize the QM calculation. |

| Density-Based Diffuse Basis Functions | Improves description of anion or excited-state electronic structures, aiding SCF convergence for challenging systems. |

| SCF Accelerators (DIIS, ADMM, RCA-DIIS) | Algorithms that extrapolate new Fock matrices from previous cycles to accelerate and stabilize Self-Consistent Field convergence. |

| Charge Balance Agents (Counterions in MM) | Maintains overall system neutrality, especially critical for electronic embedding schemes to avoid spurious electric fields. |

The QM/MM Convergence Debugging Guide: Step-by-Step Fixes for Common Failures

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My QM/MM geometry optimization fails to converge after many cycles. How do I start diagnosing the issue? A: Follow this systematic checklist to isolate the component causing the failure.

- Simplify the System: Temporarily reduce the QM region size to only the essential reacting atoms. If convergence improves, the original QM region or its method may be problematic.

- Test in Vacuum: Optimize the QM region alone, in vacuum, using the same QM method and basis set. Failure here points to a QM method issue (e.g., insufficient basis set, SCF convergence problems).

- Test the MM Field: Optimize the entire system using only the MM force field. Failure here indicates a problem in the MM parameters or structural conflicts (e.g., van der Waals clashes).

- Check the Boundary: If steps 2 and 3 succeed individually, the issue likely lies at the QM/MM boundary. Examine link atom placement, charge redistribution schemes, and any constraints applied across the boundary.

Q2: I observe unphysical bond lengths or angles specifically near the QM/MM boundary during optimization. What are the common causes? A: This is a classic boundary artifact. Key causes and checks include:

- Link Atom Handling: Ensure the link atom does not participate in the MM energy calculation and that its forces are properly projected back to the frontier atoms.

- Electrostatic Embedding: If using electrostatic embedding, verify the partial charge assignment on the MM frontier atom. An inaccurate charge can create strong, spurious electric fields.

- Constraints and Restraints: Overly tight constraints on MM atoms near the boundary can force the QM region into an unnatural geometry. Consider using harmonic restraints instead, with carefully chosen force constants.

Q3: My optimization converges, but the final structure has an abnormally high energy or shows unexpected chemical behavior. What should I verify? A: Convergence does not guarantee correctness. Perform these post-convergence checks:

- Gradient Norm: Confirm the final gradient norm is truly below the convergence threshold (typically < 0.001 a.u.). A "converged" structure with a high residual gradient is trapped.

- Single-Point Energy Check: Perform a high-level single-point energy calculation on the optimized geometry. A large discrepancy from the QM/MM energy may indicate method incompatibility or boundary-induced strain.

- Hessian Calculation: Compute the vibrational frequencies at the optimized geometry. The presence of significant imaginary frequencies (> -50 cm⁻¹) indicates a saddle point, not a minimum.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolating QM Method Failures

- Extract the coordinates of the QM region atoms from the initial QM/MM structure.

- In a standalone quantum chemistry package (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA), set up a geometry optimization using the identical QM theory and basis set as in the QM/MM simulation.

- Disable all solvent or external field models. Run the optimization.

- Analysis: Compare the convergence behavior and final geometry to the QM/MM result. Non-convergence implicates the QM method.

Protocol 2: Stress-Testing the MM Force Field

- Using the full initial system, perform a classical energy minimization (e.g., with

sander,GROMACS) using only the MM force field. - Apply the same position restraints/constraints used in the QM/MM setup on any frozen atoms.

- Run until convergence to a gradient tolerance of 0.01 kcal/mol/Å.

- Analysis: Examine the minimized structure for severe clashes or distorted bonded terms. Failure suggests corrupted parameters or initial strain.

Protocol 3: Validating the QM/MM Electrostatic Interface

- After a "successful" QM/MM optimization, calculate the electrostatic potential (ESP) of the QM region using a higher-level theory.

- Compare this ESP to the potential generated by the MM partial charges of the surrounding environment at the QM atom positions.

- Analysis: Large, systematic deviations, especially near the boundary, indicate poor charge fitting or missing polarization effects.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common QM/MM Optimization Failure Symptoms and Probable Causes

| Symptom | Probable Locus | Primary Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Early SCF non-convergence | QM Method | Basis set size, electron configuration, convergence accelerators (DIIS). |

| Large oscillations in bond lengths near cycle limit | QM Method or Boundary | Increase optimization step size limit; check link atom force projection. |

| Sudden energy spike followed by crash | MM Force Field or Boundary | Check for atoms approaching too closely (vdW clash); review boundary atom types. |

| Converged to high gradient (>0.1 a.u.) | All | Check for conflicting constraints; simplify system (Protocol 1 & 2). |

| Converged but has imaginary frequencies | QM Method or Boundary | Perform frequency analysis; follow imaginary mode to adjust initial geometry. |

Table 2: Performance of Different QM/MM Boundary Treatments on a Test System (S-Nitrosylation Reaction)

| Boundary Treatment | Avg. Optimization Cycles to Converge | Final Gradient Norm (a.u.) | Max. Distortion at Link Bond (Å) | Comp. Time (Rel.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Link Atom | 45 | 0.0008 | 0.012 | 1.00 |

| Charge Shift (1-2-3) | 38 | 0.0005 | 0.008 | 1.05 |

| Frozen Orbital | 52 | 0.0010 | 0.003 | 1.30 |

| Mechanical Embedding Only | 25 | 0.0003 | 0.021 | 0.85 |

Mandatory Visualization

Title: Diagnostic Flowchart for QM/MM Convergence Failure

Title: Standard QM/MM Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for QM/MM Diagnostics

| Item | Function in Diagnostics |

|---|---|

| High-Precision QM Software (e.g., ORCA, Gaussian, GAMESS) | Isolate and test the QM region's convergence behavior in vacuum (Protocol 1). |

| Robust MM Engine (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, GROMACS) | Stress-test the force field and initial structure for clashes (Protocol 2). |

| QM/MM Interface Code (e.g., ChemShell, QSite, interface scripts) | Implement and compare different boundary schemes (link atoms, electrostatic models). |

| Geometry Analysis Tool (e.g., VMD, PyMOL, cpptraj) | Visualize bond distortions, boundary artifacts, and structural evolution. |

| Frequency Analysis Module | Perform vibrational analysis on optimized structures to confirm a true minimum. |

| Partial Charge Fitting Tool (e.g., RESP, Merz-Singh-Kollman) | Refit MM charges for boundary atoms if electrostatic interaction is suspect. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: What are the most common signs of an unstable QM/MM interface during geometry optimization?

A: Common signs include:

- Convergence Failure: The optimization cycle fails to converge, often with oscillations in energy or maximum force/residual.

- Unphysical Geometry: Severe distortion or "kinking" of covalent bonds near the boundary, particularly involving the link atom.

- Energy Drift: A systematic, non-physical change in total energy during molecular dynamics (MD) simulations post-optimization.

- High Forces on Border Atoms: Exceptionally large forces reported on MM atoms directly bonded to QM region atoms (the border atoms).

Q2: How do I adjust Link Atom parameters to improve convergence?

A: Link atoms (typically hydrogen) are used to cap the QM region's dangling bonds. Incorrect parameters cause instability.

- Issue: Link atom position creates strain.

- Solution: The link atom position (rLA) is typically defined along the vector connecting the QM (CQM) and MM (CMM) carbon atoms: rLA = rCQM + f * (rCMM - rCQM).

- Adjust the scaling factor

f. The default is often 0.72 (scaling by van der Waals radii). Try values between 0.65 and 0.75 to minimize forces. - Use a charge redistribution scheme (e.g., charge shift, Gaussian delocalization) to prevent over-polarization. Ensure the MM bond charge is properly removed.

- Adjust the scaling factor

Table 1: Common Link Atom Schemes & Parameters

| Scheme | Scaling Factor (f) |

Charge Treatment | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Scaling | 0.70 - 0.72 | MM charge deleted | Standard organic backbones |

| Distance-Based | Dynamic (by bond type) | Charge shifted to adjacent MM atom | Mixed organic/metalloprotein systems |

| Gaussian Delocalization | Not applicable (link is virtual) | Smeared via Gaussian functions | High-level QM/MM-MD |

Q3: When and how should I apply constraints to border atoms?

A: Constraining border MM atoms can rigidify the interface, allowing the QM region to relax.

- Issue: The MM force field over-pulls on the QM region.

- Protocol:

- Identify: Select all MM atoms within 3 Å of any QM atom and directly bonded to the QM region.

- Apply Restraints: Use harmonic positional restraints with a force constant (

k). Start with a strong constant (e.g., 1000 kcal/mol/Ų). - Optimize: Run initial optimization cycles with these restraints active.

- Release: Gradually reduce

kover subsequent optimizations (e.g., 1000 → 100 → 10 → 0) in a multi-stage protocol. - Validate: Monitor the final forces on border atoms; they should be comparable to typical MM forces.

Q4: My QM/MM optimization oscillates without converging. What is a systematic procedure to address this?

A: Follow this structured workflow:

Diagram Title: Workflow for Resolving QM/MM Optimization Oscillations

Q5: What specific convergence criteria should I tighten for QM/MM?

A: Standard criteria may be too loose. Tighten these thresholds:

- Maximum Force: ≤ 0.00045 Hartree/Bohr (≈ 0.001 eV/Å)

- RMS Force: ≤ 0.0003 Hartree/Bohr

- Maximum Displacement: ≤ 0.0018 Å

- RMS Displacement: ≤ 0.0012 Å

Table 2: Recommended QM/MM Convergence Thresholds

| Criterion | Standard MM | Tight QM/MM | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Force | 0.001 | 0.00045 | Hartree/Bohr |

| RMS Force | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | Hartree/Bohr |

| Max Displacement | 0.004 | 0.0018 | Ångstrom |

| RMS Displacement | 0.002 | 0.0012 | Ångstrom |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for QM/MM Interface Tuning

| Item | Function in Interface Softening |

|---|---|

| Positional Restraint Primitives | Harmonic potential functions (in MD code) to constrain border MM atoms during early optimization stages. |

| Link Atom Tuning Scripts | Custom scripts (Python, Bash) to algorithmically vary the scaling factor f and scan for minimal interface strain. |

| Force Decomposition Analysis Tool | Utility to parse output files and separate forces on QM atoms, link atoms, and border MM atoms for diagnosis. |

| Charge Redistribution Library | Implemented methods (e.g., CHELPG, RESP fitting for model systems) to correctly handle MM charge removal near the cut. |

| Multi-Stage Optimization Template | A pre-configured input file template that defines sequential optimization jobs with decreasing restraint strengths. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Queue | Access to sufficient CPU/GPU resources for the increased cost of tighter convergence and multiple tuning runs. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My QM/MM geometry optimization stalls after a few iterations. The energy change is negligible, but the gradient norm remains high. What should I do? A1: This indicates a possible convergence issue near a saddle point or on a shallow plateau. First, check the gradient norm reported by your software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, AMBER). If it's above the convergence threshold (typically 0.001 au for QM regions), try switching algorithms. Steepest Descent is robust but slow; switch to Conjugate Gradient (CG) or L-BFGS to overcome this. Increase the iteration limit for the minor optimization cycle (e.g., from 50 to 200). Verify your QM/MM partitioning; an unstable MM region may feed noise into the QM gradients.

Q2: When using L-BFGS in my protein-ligand system, the optimization crashes with "non-positive definite matrix" errors. How can I resolve this? A2: This error in L-BFGS often arises from numerical inaccuracies in the approximated inverse Hessian, especially with noisy QM/MM gradients. Recommended actions:

- Restart L-BFGS: Reset the Hessian approximation by clearing the history (set

NCorrections=5or lower in some packages). - Increase Step Size Control: Implement a stricter line search (e.g., Wolfe conditions) or reduce the initial step size (

MaxStepin many codes) by 50%. - Switch Algorithm Temporarily: Perform 10-20 steps of Steepest Descent or Conjugate Gradient to get closer to a minimum, then restart L-BFGS.

- Check Gradients: Ensure your QM method (e.g., DFT, semi-empirical) and MM force field are compatible and gradients are consistent.

Q3: How do I choose an initial step size (alpha) when switching from Steepest Descent to Conjugate Gradient for a large QM/MM system? A3: The initial step size is critical. Use an empirical protocol based on the previous algorithm's behavior:

- Let the final step size from your Steepest Descent run be

α_sd. - Calculate the ratio of gradient norms:

R = |g_new| / |g_old|. - Set the initial CG step size

α_cg = α_sd * min(1.2, max(0.5, R)). This scales the step based on local curvature changes. - Always use a backtracking line search (e.g., Armijo rule) for the first 5 CG steps to adapt. Monitor energy; if it increases, immediately halve

α_cg.

Q4: My optimization oscillates between two structures, especially in the MM solvent region. Is this a step size or algorithm problem? A4: Oscillation suggests an oversized step causing overshoot. This is common in flexible MM environments. Implement adaptive step size control:

- If energy increases for 2 consecutive steps:

α_new = 0.8 * α_old. - If energy decreases monotonically for 5 steps: