The Methane Makeover: A Tiny Reactor's Big Dream for Cleaner Chemicals

Imagine turning the primary component of natural gas directly into one of the world's most essential industrial chemicals, all in a device the size of a book.

Article Navigation

Formaldehyde is the invisible workhorse of the modern world. It's in the glue that holds your furniture together, the resins in your car's brakes, and the insulation in your walls. But making it has traditionally been a complex, multi-step, and energy-intensive process. Now, a revolutionary technology—the microchannel reactor—is paving the way for a simpler, greener method: converting methane (natural gas) directly into formaldehyde in a single, swift step, without the need for expensive catalysts. Let's dive into the science of how this tiny titan is set to overhaul a giant industry.

Why Fix a Process That Isn't Broken?

The classic way to make formaldehyde is a two-step tango. First, methane (or another source like methanol) is reformed with steam to make syngas (a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide). Second, this syngas is fed into another reactor where it's converted into formaldehyde using a catalyst. It works, but it's bulky, requires two separate massive plants, and the catalysts can be expensive, toxic, and prone to degrading.

The dream has always been a direct, single-step process. Cut out the middleman! React methane and oxygen directly to get formaldehyde. The chemical equation looks deceptively simple:

The problem? Methane is an incredibly stable molecule. Breaking its strong C-H bonds requires a lot of energy, and that same energy can easily overreact with the delicate formaldehyde product, burning it completely into useless carbon dioxide (CO2). It's like trying to gently toast a single marshmallow in a bonfire—the window between "raw" and "ash" is frustratingly narrow. This is where the microchannel reactor enters the story.

The Magic of the Microchannel Reactor

Think of a computer chip, but for chemistry. Instead of silicon pathways for electrons, a microchannel reactor has tiny, hair-thin pathways (often smaller than a millimeter wide) for chemicals to flow. This miniature scale is its superpower.

- Precision Control: The small size allows for exquisite control over reaction time—the chemicals are in the hot zone for mere milliseconds. This lets engineers zap the methane just enough to start the reaction but kick the products out before they have time to overreact.

- Superior Heat Management: The high surface-area-to-volume ratio means heat can be added or removed incredibly efficiently, preventing runaway "hot spots" that would ruin the product.

- Enhanced Safety: Operating with such small volumes of chemicals at any given moment makes the process inherently safer than large-scale traditional reactors.

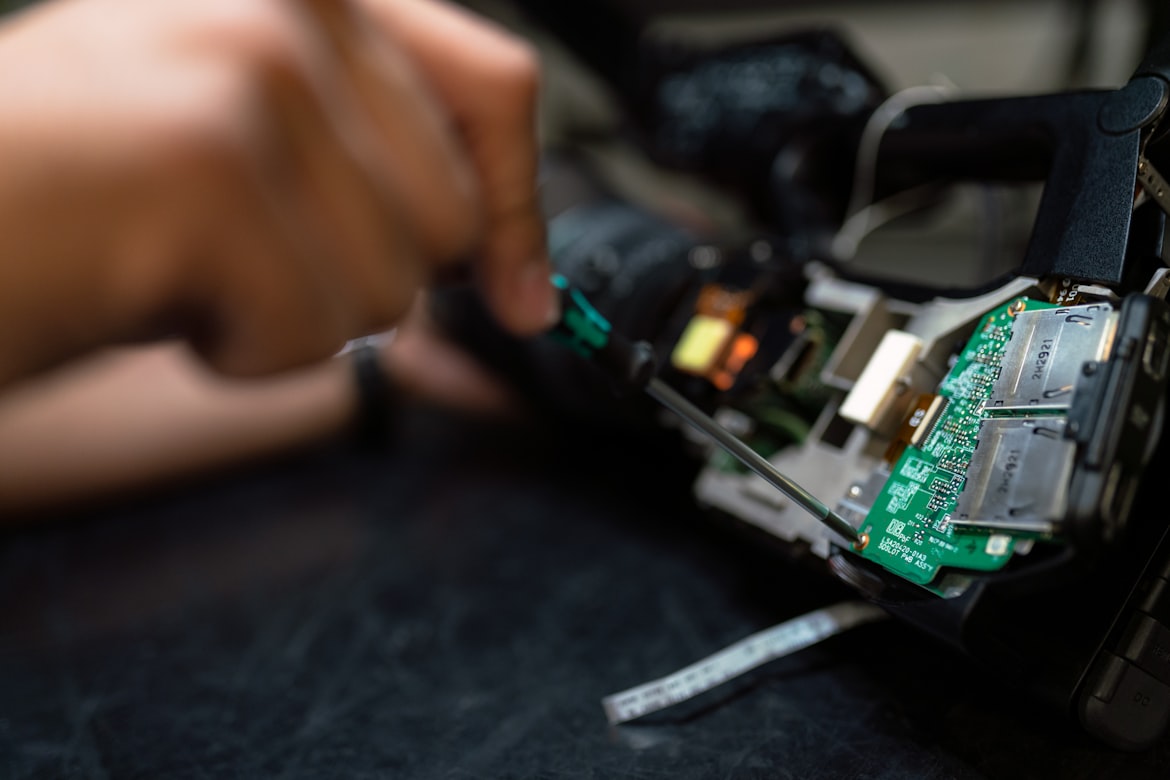

Microchannel reactors feature intricate networks of tiny passages for chemical reactions.

By exploiting these features, scientists theorized they could finally tame the wild direct methane-to-formaldehyde reaction.

A Deep Dive: Simulating the Perfect Reaction

While building and testing a physical microreactor is key, much of the pioneering work happens inside a supercomputer. Scientists use sophisticated software to model the fluid dynamics and chemical kinetics inside these tiny channels. Let's look at a theoretical, yet crucial, computational experiment that proves the concept.

Objective: To determine the optimal conditions of temperature, pressure, and reaction time ("residence time") within a silicon-carbide microchannel reactor to maximize formaldehyde yield from methane and oxygen, while minimizing CO2 production.

Methodology: A Step-by-Step Simulation

- Design the Virtual Reactor: Researchers create a digital model of a single microchannel, precisely defining its dimensions (e.g., 500 µm wide, 250 µm deep, 2 cm long).

- Define the Feed: The simulated reactant mixture is set—for example, a specific ratio of methane to oxygen, often diluted with an inert gas like nitrogen to help control the reaction's temperature.

- Set the Conditions: The reactor wall temperature is set to a high value, typically between 600°C and 800°C, to provide the energy needed to activate the stubborn methane molecules.

- Run the Simulation: The computer solves millions of equations calculating how the gases flow, how heat transfers, and how every possible chemical reaction (a network of 50+ steps!) proceeds as the mixture zips through the channel.

- Analyze the Output: The software outputs the composition of the gas exiting the virtual reactor, telling the scientists exactly how much formaldehyde was produced versus unwanted CO2.

Results and Analysis: Finding the Sweet Spot

The core finding of these simulations is the existence of a very precise "operational window." The following data visualizations illustrate the critical balance required for successful conversion.

Temperature vs. Yield

Figure 1: Formaldehyde yield is highly sensitive to temperature, with a narrow optimal range.

Residence Time Impact

Figure 2: The precise control of reaction time is crucial to prevent product decomposition.

The Temperature Tightrope Walk

(Fixed Conditions: Pressure = 2 atm, Residence Time = 10 ms, CH4:O2 Ratio = 4:1)

| Temperature (°C) | Formaldehyde Yield (%) | CO2 Selectivity (%) | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 600 | 2.1 | 15 | Too cold. Methane doesn't react well. |

| 650 | 5.8 | 28 | The "Sweet Spot" Best balance of yield and selectivity. |

| 700 | 4.3 | 55 | Too hot. Formaldehyde breaks down rapidly into CO2. |

| 750 | 1.5 | 82 | Way too hot. Almost everything burns to CO2. |

Table 1: This shows that a window of about 640-660°C is critical for success.

The Need for Speed - Importance of Residence Time

(Fixed Conditions: T = 650°C, Pressure = 2 atm, CH4:O2 Ratio = 4:1)

| Residence Time (Milliseconds) | Formaldehyde Yield (%) | What's Happening Inside |

|---|---|---|

| 5 ms | 3.5 | Not enough time for the reaction to complete. |

| 10 ms | 5.8 | Optimal time. Products exit before they decompose. |

| 20 ms | 4.0 | Too long. Formaldehyde is over-oxidizing to CO2. |

| 50 ms | 1.2 | Far too long. Yield is destroyed. |

Table 2: This proves the microreactor's core advantage: ultra-precise control over timing.

Scientific Importance: These simulated results are a blueprint. They provide a critical proof-of-concept, showing that high selectivity for formaldehyde is possible under non-catalytic conditions if the reaction conditions are exquisitely controlled—a feat only achievable with a microchannel reactor. This saves immense time and resources before engineers even start machining metal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Building a Micro-Reaction

What would you need to run the real-world version of this experiment? Here's a look at the essential research reagents and materials.

High-Purity Methane (CH4)

The primary feedstock. Its purity is essential to avoid side reactions with impurities that could poison the process or clog the microchannels.

High-Purity Oxygen (O2)

The oxidizing agent. It must be carefully metered to provide enough to make formaldehyde but not so much that it causes combustion.

Inert Diluent Gas (e.g., N2, He)

Used to dilute the reactant mixture, absorbing and distributing heat to prevent explosive hot spots and to help control residence time.

Silicon Carbide (SiC) Reactor

The material of choice for building the microchannels. It's inert, extremely resistant to high temperatures, and an excellent conductor of heat.

Mass Flow Controllers

Hyper-precise electronic valves that control the flow rate of each gas down to tiny fractions of a milliliter per minute, ensuring perfect recipe ratios.

Mass Spectrometer / Gas Chromatograph

The "eyes" of the operation. These analytical instruments instantly analyze the product stream coming out of the reactor.

A Glimpse into a Greener Future

The direct, non-catalytic conversion of methane to formaldehyde in microchannel reactors is more than a laboratory curiosity. It represents a paradigm shift towards distributed, intensified chemical manufacturing. Instead of a sprawling chemical plant, you could have a refrigerator-sized unit located right at a natural gas well, converting the resource directly into a high-value product on-site.

While challenges remain in scaling up the number of microchannels and managing long-term stability, the theoretical analysis is overwhelmingly positive. This tiny technology holds the giant promise of making the chemical industry safer, more efficient, and significantly more sustainable, one microscopic channel at a time.

The future of chemical production: compact, modular, and located where the resources are.